Introduction to the Fall Armyworm

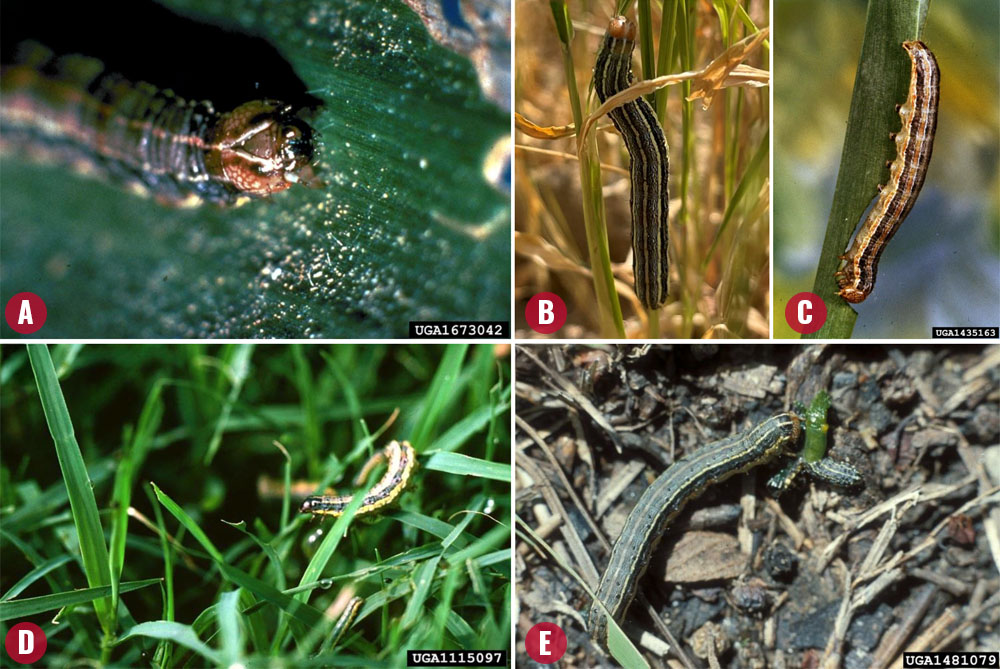

The fall armyworm (Figure 1), Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith), is native to North America. Fall armyworm caterpillars are identified with an inverted Y-shaped marking on their head capsule (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Late-Stage Fall Armyworm Caterpillars.

Figure 1. Late-Stage Fall Armyworm Caterpillars.

Photos: A. Steve L. Brown, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; B. Robert Wolverton; C. Clemson University – USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series, Bugwood.org; D. Charles T. Bryson, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org; E. Frank Peairs, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org.

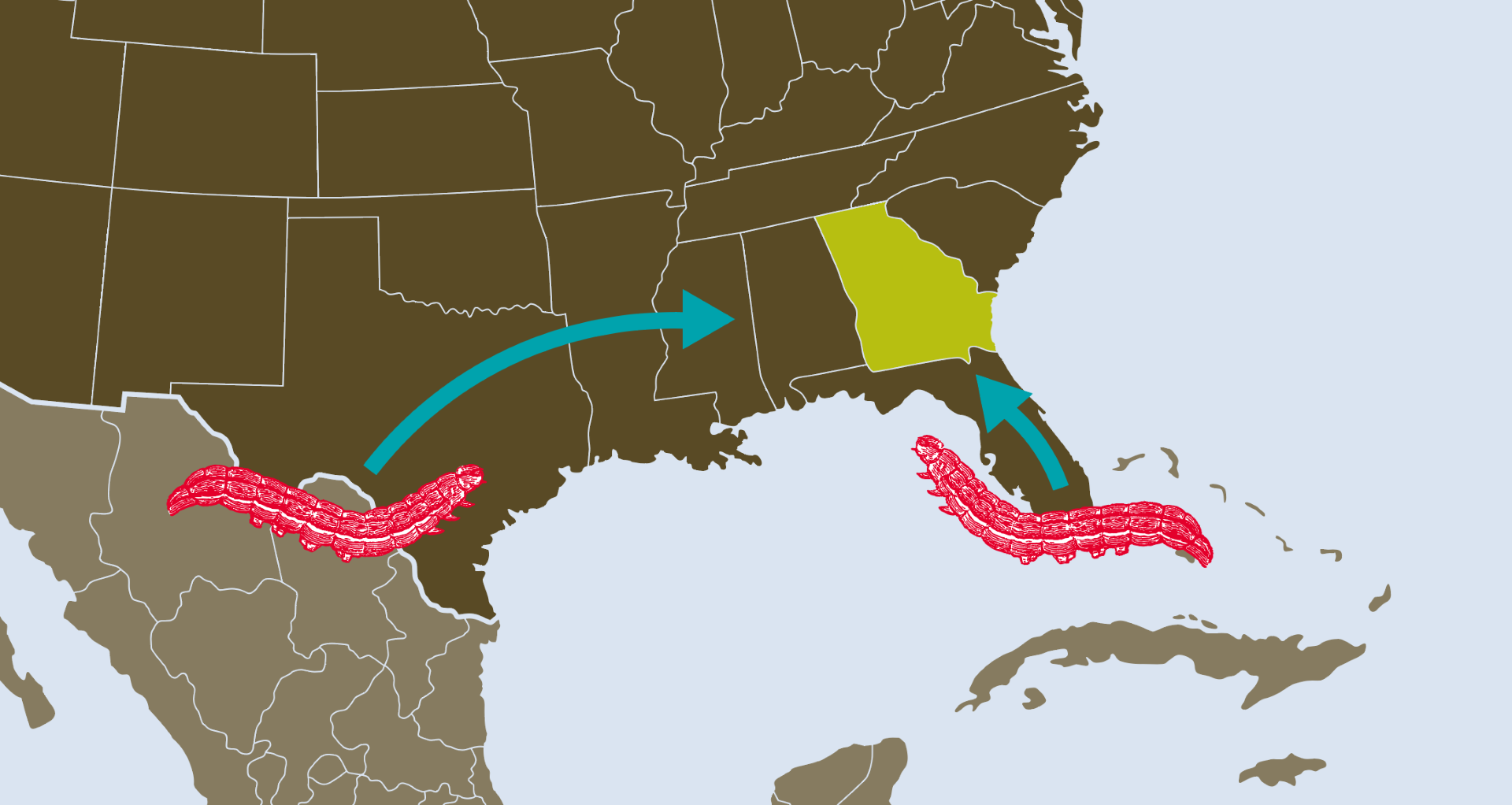

Fall armyworms are active throughout the year in the tropical regions of Florida (from Tampa to Miami), southern Texas, and northern Mexico. Fall armyworm moths are dispersed yearly from these regions to the eastern and midwestern U.S. states, including Georgia, through weather fronts, such as storms and wind currents (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Annual Dispersal of Fall Armyworm Moths. Every year, these pests are dispersed north and east through storms and air currents coming from southern Florida and Texas during the late spring and summer.

Figure 2. Annual Dispersal of Fall Armyworm Moths. Every year, these pests are dispersed north and east through storms and air currents coming from southern Florida and Texas during the late spring and summer.

Map: Lavi Astacio.

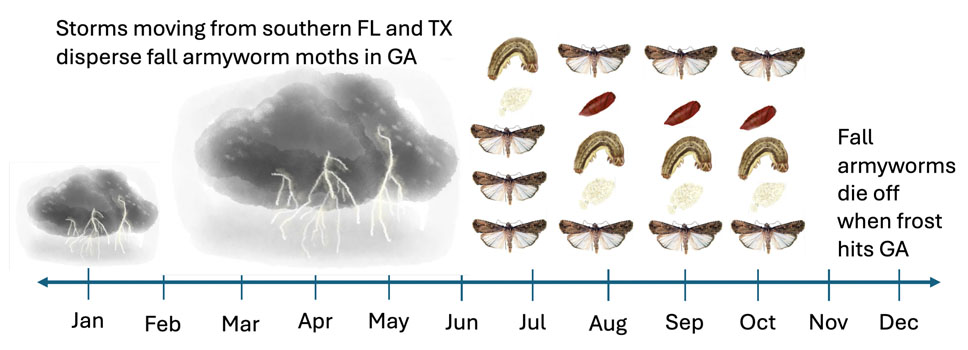

They reach Georgia in the spring or early summer, and caterpillars are noticeable in turfgrass mostly in early July. The exact timing of their arrival in Georgia from tropical regions is subject to weather conditions and varies every year (Figure 3). In years when a larger number of storms occur in Florida and move toward the North, more moths tend to arrive, and a high population of them land in Georgia.

Regardless of their arrival time, fall armyworm moths can go through at least two or three generations in Georgia, and their populations will grow rapidly during the summer and fall (Figure 3). Wet weather conditions in the summer increase the chances for the young, tiny stages of these caterpillars to survive and flourish (compared to drought conditions). However, relatively dry conditions with high temperatures support older caterpillars—they thrive in the summer. By the end of the fall, entire fall armyworm populations in Georgia die out because they cannot survive freezing conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Timeline of the Fall Armyworm Problem in Georgia. Fall armyworm moth photo: Robert J. Bauernfeind, Kansas State University, Bugwood.org; Illustration: Theresa Villanassery.

Figure 3. Timeline of the Fall Armyworm Problem in Georgia. Fall armyworm moth photo: Robert J. Bauernfeind, Kansas State University, Bugwood.org; Illustration: Theresa Villanassery.

Lifecycle of Fall Armyworms

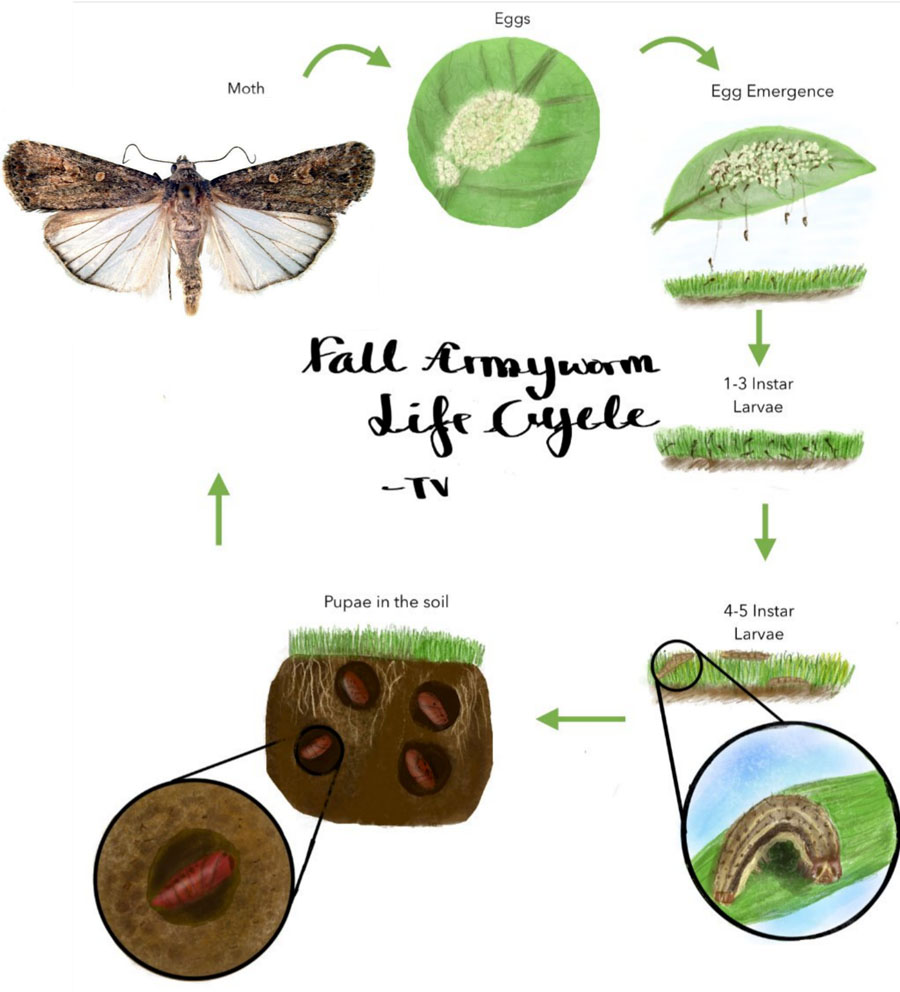

Figure 4. Lifecycle of Fall Armyworms.

Figure 4. Lifecycle of Fall Armyworms.

Illustration: Theresa Villanassery; moth photo: Robert J. Bauernfeind, Kansas State University, Bugwood.org.

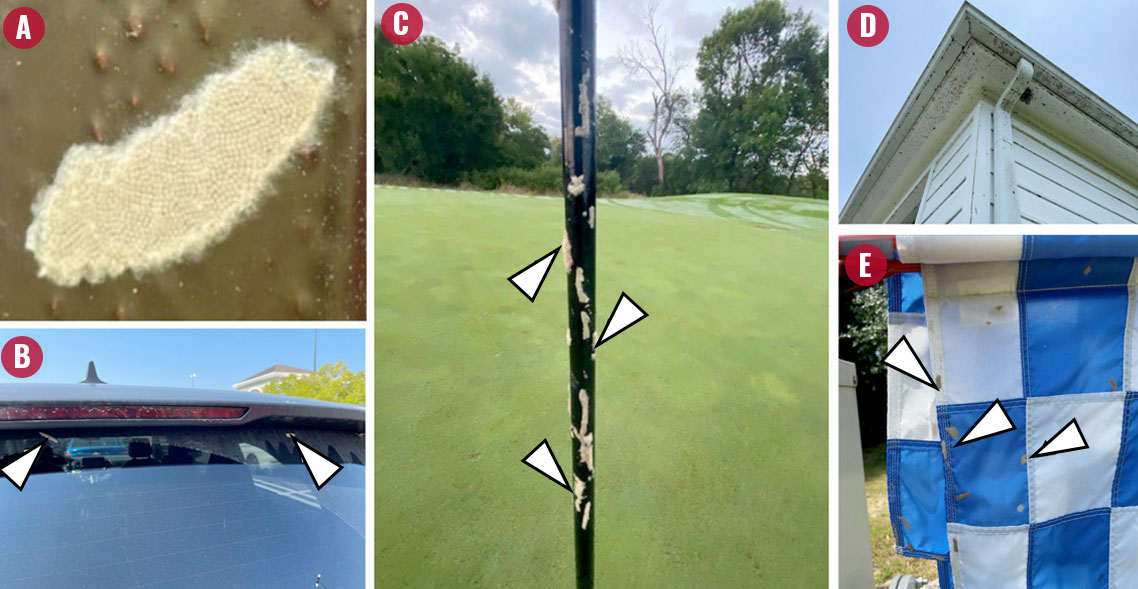

The lifecycle of the fall armyworm is illustrated in Figure 4. Fall armyworm moths are active at night. After mating, they lay eggs in batches (called egg masses). A single egg mass consists of 50–200 eggs, and it appears as a cottony, fuzzy patch (Figure 5A) on a surface. For example, if you see 10 egg masses near a lawn, approximately 1,000 fall armyworm caterpillars will be available to infest that lawn.

The moths lay eggs on any surface or structure near a lawn—such as a flag, fence, pole, storage shed, barn, exterior wall (of a house), trees along a wood line, on plants in a garden, on a patio, etc. (Figures 5B–E and 6). All eggs in each mass hatch within 2–3 days, at about the same time.

Figure 5. Egg Masses Deposited on a (A) Patio, With About 200 Eggs; (B) Car, (C) Pole, (D) Storage Shed, and (E) Flags. Egg masses are indicated by black and white arrows. Photos: A. and B. Shimat V. Joseph; C. Lisa Ames; D. and E. Robert Wolverton.

Figure 5. Egg Masses Deposited on a (A) Patio, With About 200 Eggs; (B) Car, (C) Pole, (D) Storage Shed, and (E) Flags. Egg masses are indicated by black and white arrows. Photos: A. and B. Shimat V. Joseph; C. Lisa Ames; D. and E. Robert Wolverton.

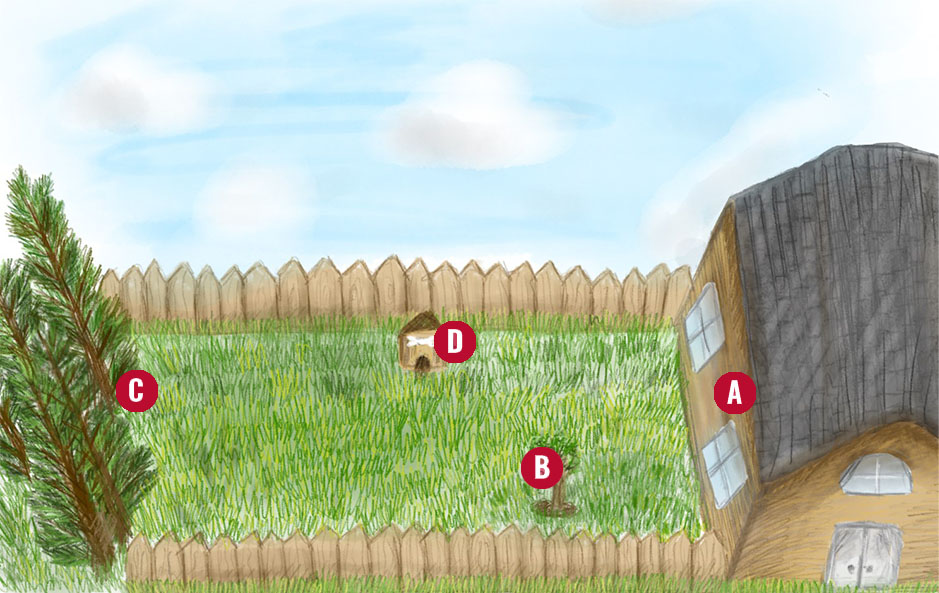

Figure 6. Typical Egg Laying Sites. (A) On the siding of a home, (B) on a small tree, (C) on taller trees, and (D) on a dog house. They can be found on any site near turfgrass. Illustration: Theresa Villanassery.

Figure 6. Typical Egg Laying Sites. (A) On the siding of a home, (B) on a small tree, (C) on taller trees, and (D) on a dog house. They can be found on any site near turfgrass. Illustration: Theresa Villanassery.

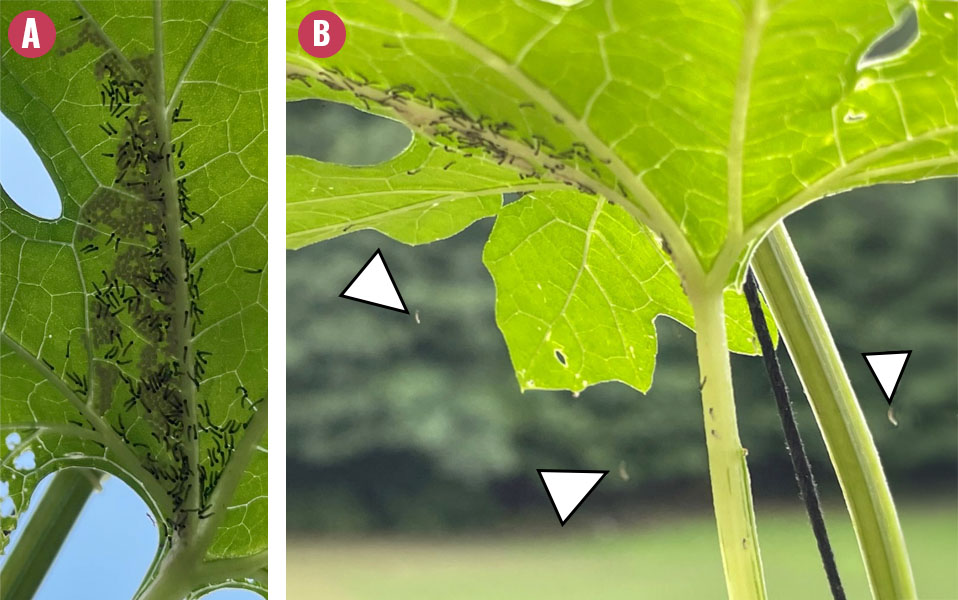

These tiny caterpillars aggregate for some time where their eggs were laid (Figure 7A), then leave the site using a thin web to lower themselves and land on turfgrass (Figure 7B). Caterpillars must feed on the grass within a few hours after their eggs hatch. Young caterpillars remain inside the turfgrass canopy and feed on grass blades, mostly at night. They reach 2 in. in length when they grow into the fourth and fifth caterpillar stages (see Figure 4).

Figure 7. Caterpillars Hatch and Disperse. The eggs hatch into first-stage fall armyworm caterpillars (A) and disperse using a thin web (B) to lower themselves onto the turfgrass (indicated by white arrows). Photos: Shimat V. Joseph.

Figure 7. Caterpillars Hatch and Disperse. The eggs hatch into first-stage fall armyworm caterpillars (A) and disperse using a thin web (B) to lower themselves onto the turfgrass (indicated by white arrows). Photos: Shimat V. Joseph.

Late-stage caterpillars are aggressive feeders and are active during both the day and night. In the summer, they take 2 to 3 weeks to reach the pupal stage. The fifth-stage caterpillars drop from leaves onto the soil surface, and then they bore into the soil for pupation (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Pupa of Fall Armyworm in Soil. Photo: Shimat V. Joseph.

Figure 8. Pupa of Fall Armyworm in Soil. Photo: Shimat V. Joseph.

In this inactive and nonfeeding stage, dark brown pupae remain in the soil for a little over a week before emerging as moths (Figure 9). After a week, the newly emerged adults mate and start laying eggs again. During the summer months in Georgia, one generation (from egg to moth) is completed within 4 weeks.

Figure 9. Moth of Fall Armyworm. Photos: A. William Lambert, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; B. John Capinera, University of Florida, Bugwood.org; C. Lyle Buss, University of Florida, Bugwood.org.

Figure 9. Moth of Fall Armyworm. Photos: A. William Lambert, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org; B. John Capinera, University of Florida, Bugwood.org; C. Lyle Buss, University of Florida, Bugwood.org.

Fall armyworm moths can be found everywhere in Georgia during the summer. It is considered a sporadic pest because they are introduced every year from Florida and Texas (they do not overwinter in Georgia). The timing and intensity of infestation can vary from location to location.

Fall Armyworm Caterpillar Damage

The third, fourth, and fifth stages of fall armyworm caterpillars (see Figure 1) are destructive to turfgrass. The younger stages (first through third larval stages) are so tiny that it is hard to see if the turfgrass is infested with fall armyworms. The green turfgrass will gradually turn brown as the caterpillars grow into the third, fourth, and fifth larval stages. The damaged turfgrass may appear diseased or like it experienced drought (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Feeding Damage From Fall Armyworm Caterpillars on Bermudagrass Lawns. Photos: A. Ryan Hodgson; B. & E. Shimat V. Joseph; C. Robert Wolverton; D. Brian Schwartz.

Figure 10. Feeding Damage From Fall Armyworm Caterpillars on Bermudagrass Lawns. Photos: A. Ryan Hodgson; B. & E. Shimat V. Joseph; C. Robert Wolverton; D. Brian Schwartz.

Young caterpillars do well with some moisture (from rain), but late-stage caterpillars do well with dry conditions. Often, moths are introduced to Georgia through back-to-back storms in the spring, and when the egg masses hatch, it is mostly during moist conditions.

Fall armyworm caterpillars tend to do less damage to healthy turfgrass. Proper fertilizer application, regular mowing, and irrigation will help produce healthy turfgrass and help to minimize fall armyworm infestations. Fertilizing with phosphorus will help to grow a strong root system that can tolerate feeding damage from fall armyworm caterpillars when that occurs.

After mild to moderate infestations, the affected turfgrass usually grows back within 3–4 weeks with proper fertilization and irrigation. Resodding may be required after severe infestations (Figure 11), such as when caterpillars feed on the entire stolon (stem) of the turfgrass.

Figure 11. Severe Fall Armyworm Caterpillar Infestation. Photo: Robert Wolverton.

Figure 11. Severe Fall Armyworm Caterpillar Infestation. Photo: Robert Wolverton.

Monitoring for Armyworms

Because the fall armyworm problem recurs each year from July to September, but the incidence is sporadic, the first and best early detection strategy is to check for the presence of egg masses. Check for egg masses on any structure near turfgrass (see Figures 5 and 6). No threshold exists that correlates with damage. With a greater number of egg masses, a greater number of caterpillars will emerge and the more damage they will cause. Use band applications of insecticides when you see many egg masses.

Take the second monitoring approach when you see any signs of feeding damage on the turfgrass. The damage is usually initiated in turfgrass near the edge or a border of a structure where eggs are laid (Figures 5 and 6). Drench or pour soap water into the brown turfgrass where you see the initial damage on the lawn edges (Figure 12). If present, later stages of fall armyworm caterpillars will wiggle out from the turfgrass. Please take immediate action if the damage was due to fall armyworm feeding, as this will reduce further damage to turfgrass.

Figure 12. Monitoring Before or After Insecticide Application by Pouring Soapy Water on Turfgrass. If fall armyworm caterpillars are present, they will emerge onto the turfgrass surface. From “Controlling Fall Armyworms on Lawns and Turf,” by K. Kesheimer, D. Held, and P. Cobb, 2021, Alabama Cooperative Extension, p. 3 ().

Figure 12. Monitoring Before or After Insecticide Application by Pouring Soapy Water on Turfgrass. If fall armyworm caterpillars are present, they will emerge onto the turfgrass surface. From “Controlling Fall Armyworms on Lawns and Turf,” by K. Kesheimer, D. Held, and P. Cobb, 2021, Alabama Cooperative Extension, p. 3 ().

Management of Fall Armyworms in Georgia

Early detection through monitoring egg masses on structures should indicate fall armyworm activity in an area starting in July in Georgia. At this stage, they are likely young caterpillars (first- to third-stage larvae) hiding inside the turfgrass canopy. Band application of insecticides such as Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki (sometimes seen as Btk) or pyrethroid insecticides, such as bifenthrin, permethrin, deltamethrin, etc., around structures will help.

Predators—especially ants, ground beetles, and earwigs—are abundant in turfgrass. Maintaining turfgrass with minimal insecticide application will help healthy predator populations in turfgrass. Predators are active during nighttime and are effective even at high temperatures during Georgia’s summers. However, the sudden, overwhelming population of fall armyworm infestations in the late summer or fall requires insecticide applications. Similarly, parasitoids (tiny hymenopteran wasps or tachinid flies) can parasitize fall armyworm caterpillars, but high infestations make it difficult to catch up.

Once caterpillars increase in size, chlorantraniliprole insecticide might be the best option. Tetraniliprole insecticide is an additional option for golf courses and athletic fields that can effectively reduce fall armyworm caterpillars. Pyrethroid insecticides may not provide adequate control when caterpillars are in their late stages.

Insecticides that function as insect growth regulators, such as diflubenzuron, pyriproxyfen, and azadirachtin, could be added along with pyrethroids to improve efficacy—insect growth regulators are effective in inhibiting the growth of caterpillars, especially on second- and third-stage caterpillars. Pouring soapy water regularly on affected spots in the turfgrass where the applications were made will help you track if the application reduced the caterpillar activity. The number of caterpillars emerging from turfgrass should be lower after days of application.

Bermudagrass is a popular turfgrass type in Georgia and is susceptible to fall armyworm caterpillar infestation. Bermudagrass cultivar ‘TifTuf’ can tolerate some attacks compared to other bermudagrass cultivars since it grows faster. Fall armyworm caterpillar infestation is lower or limited on zoysiagrass (such as ‘Zeon’, ‘Emerald’, and ‘Zenith’) than on bermudagrass or centipedegrass. St. Augustinegrass is also susceptible to fall armyworm infestations.

If new sod is planted, make sure it is regularly monitored for armyworms using soapy water and that immediate insecticide applications are made as new sod is more vulnerable to fall armyworm infestation than already established turfgrass. Please refer to the 禁漫天堂 Extension publication C 1130, Armyworms in Sod if you planted new sod and it is infested with fall armyworm caterpillars.

For more specific insecticide recommendations, consult the or your local county Extension agent. Please read the label before using any insecticides, as the label is the law.

References

Braman, S. K., Duncan, R. R., Hanna, W. W., & Engelke, M. C. (2004a). Integrated effects of host resistance and insecticide concentration on survival of and turfgrass damage by the fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of Entomological Science, 39(4), 584–597.

Braman, S. K., Duncan, R. R., Hanna, W. W., & Engelke, M. C. (2004b). Turfgrass species and cultivar influences on survival and parasitism of fall armyworm. Journal of Economic Entomology, 97(6), 1993–1998.

Khan, F. Z. A., & Joseph, S. V. (2022). Assessment of predatory activity in residential lawns and sod farms. Biological Control, 169, 104885.

Khan, F. Z. A., & Joseph, S. V. (2024). Influence of short-term, water-deprived bermudagrass on Orius insidiosus predation and Spodoptera frugiperda larval survival and development. Biocontrol Science and Technology , 34(2), 189–202.

Nagoshi, R. N., Meagher, R. L., & Hay-Roe, M. (2012). Inferring the annual migration patterns of fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the United States from mitochondrial haplotypes. Ecology and Evolution, 2(7), 1458–1467.

Potter, D. A., & Braman, S. K. (1991). Ecology and management of turfgrass insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 36, 383–406.

Singh, G., Waltz, C., & Joseph, S. V. (2021). Potassium and nitrogen impacts on survival and development of fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of Entomological Science, 56(4), 411–423.

Status and Revision History

In Review on Jun 04, 2025

Published on Jun 17, 2025